Newsletter

Suscríbete a nuestro Newsletter y entérate de las últimas novedades.

https://centrocompetencia.com/wp-content/themes/Ceco

volver

The definition of the relevant market seeks to identify all firms that exert mutual competitive pressure —for example, those that limit a firm’s ability to raise prices, lower quality or harm innovation. In simple terms, the definition of the relevant market attempts to separate products and services that compete with each other from those that do not.

There are two dimensions in the definition of the relevant market. The first considers which products compete (relevant product market) and the second, where these products compete (relevant geographic market).

When defining a market, it will sometimes be necessary to test these boundaries using established models and accepted economic tools. These methods seek to verify if a theoretical market exists in reality; they ensure that market definitions are not too narrow or too broad, which would distort the subsequent assessment of concentration, market power, and anticompetitive effects.

Market definition is one of the primary tools of competition policy and law. It’s a tool used in most of its areas, encompassing merger review, abuses of a dominant position and vertical or horizontal agreements (OECD, 2012). Traditionally, determining the relevant market is the first step in assessing the market power of an economic agent and, with it, whether a particular conduct or operation may produce anticompetitive effects.

An accepted guiding principle for defining the relevant product market was provided by Bishop and Darcey (1995), which holds that a relevant market is one that is ‘worth monopolizing.’ Since such a market includes all substitute products, control over it would allow for a profitable increase in prices up to a monopoly level.

The extent to which firms can increase their prices above normal competitive levels depends on the possibility and willingness of consumers to buy other products (demand substitution) and the capacity and willingness of other firms to supply those products (supply substitution). The smaller the number of substitute products and/or the more difficult it is for other firms to start supplying those products, the less elastic the demand curve will be and, therefore, the more likely it is to charge higher prices.

Based on this notion, the relevant product market is determined mainly by considering two criteria: demand substitution and supply substitution.

In general, there is agreement that the focus of the analysis should be on demand substitution. As stated by the U.S. agencies —the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ)— in their 2010 “Horizontal Merger Guidelines”:

“Market definition focuses solely on demand substitution factors, i.e., on the ability and willingness to substitute one product for another in response to a price increase or a corresponding non-price change, such as a reduction in product or service quality.”

This approach is supported by experts who argue that it can be confusing and complex to take both economic forces —demand and supply substitution— into account in the same stage of analysis (Baker, 2007).

When examining potential consumer responses, what matters is the response of the marginal consumer, not the average consumer. Therefore, it is considered that a small but significant number of consumers switching to another product in response to a price increase is an indication that both goods are part of the same relevant market.

To determine the scope and level of demand substitution that would render monopolization unprofitable, it is necessary to evaluate the price elasticity of demand.

The hypothetical monopolist test, which was first introduced in the 1982 United States merger guidelines, has been used throughout time (though not without modifications), to evaluate demand substitution forces.

To define the relevant product market, it is necessary to identify close substitutes. But what should be considered a close substitute?

The most common way to identify the relevant market for a product is through the SSNIP test, which stands for “Small but Significant and Non-Transitory Increase in Price.” This econometric test is also known as the “Hypothetical Monopolist Test.”

In simple terms, one begins with a group of products that could comprise the relevant market and creates a hypothetical scenario in which a single firm controls all of these products. Next, the effect of a small but significant permanent price increase (about 5% or 10%) is simulated. If consumers react to this hypothetical price hike by buying other products, then those products must be included in the reference market and the test is repeated until significant substitution no longer exists.

What is being calculated is the residual demand elasticity of the firm —that is, how a change in the price of the firm’s product affects the demand for that product. Many variations of this test exist depending on the nature of the market under scrutiny, and there are practical difficulties in its implementation. Baker (2007) discusses these challenges in greater depth.

To carry out the hypothetical monopolist test, it is necessary to estimate the elasticity of demand and compare it with the critical elasticity. The crucial question this exercise seeks to answer is: what is the maximum magnitude of demand substitution for a price increase to remain profitable?

In the case of a SSNIP, a hypothetical monopolist faces a trade-off when increasing product prices. On one hand, profits increase due to the higher price-cost margin on the units it continues to sell after the hike (inframarginal effect). However, the price hike also has a negative effect on profits, as some consumers stop buying or substitute the products (marginal effect). The higher the elasticity of demand, the greater the negative marginal effect on profits. The sum of these opposing effects on earnings determines whether the price increase is profitable or not.

A quantitative methodology known as ‘critical elasticity’ or ‘critical loss analysis’ (CLA) has been proposed to compare these effects and define the relevant market, although the tool is not without its flaws (O’Brien & Wickelgren, 2003).

The CLA calculates the critical loss of the hypothetical monopolist —that is, the magnitude of lost sales that would make the imposition of a small but significant and non-transitory price increase unprofitable for the hypothetical monopolist— and compares it with the so-called “actual loss of sales” that would result from this increase.

If the price increase is profitable —meaning the actual loss of sales, given by the estimated elasticity, is less than the critical loss of sales— the candidate market can be considered the appropriate relevant market. Otherwise, the candidate market must be discarded.

To estimate the actual loss, direct evidence regarding the responsiveness of demand can be sought. This may include econometric studies or marketing studies. Occasionally, an intuitive assessment of qualitative facts regarding what would lead a customer to stop consuming a group of products might suffice.

The SSNIP test is not infallible.

One of the greatest risks when implementing this test is falling into the so-called ‘Cellophane Fallacy.’ This argument warns that it is not possible to accurately determine the relevant market in certain cases—for example, when high market power already exists or in the presence of collusion—given that the test would be applied based on distorted prices.

In these cases, the product’s price elasticity of demand could be a poor indicator. Faced with a price increase that is already too high, consumers would consider other products to be sufficiently good substitutes—something that would not occur if the price were lower (closer to the competitive level). This results in SSNIP test definitions that are overly broad, making concentration levels appear artificially low and leading to false predictions regarding the magnitude of market power (Schaerr, 1985).

The name of this limitation comes from the old Du Pont Case (1956). The Du Pont company argued that cellophane was not an independent relevant market because it could be demonstrated that cellophane had a high cross-price elasticity of demand with other flexible packaging materials at prevailing prices, such as aluminum foil, wax paper, and polyethylene. However, the court considered that the prevailing price of cellophane was above the competitive price, and therefore this fact could not be considered evidence of effective competitive pressure; it determined that the relevant market contained only cellophane.

There are many situations in which the SSNIP test is not viable, either due to data limitations or because the market is highly differentiated and it is not clear in what order products should be added if the initial candidate market is not appropriate.

Furthermore, to analyze two-sided markets —which are increasingly common in practice— experts argue that the traditional SSNIP test cannot be applied as is, and must be modified to take into account indirect network externalities (Hesse (2007), Filistrucchi (2008)).

Because of these externalities, digital markets often offer free services to consumers (at least in monetary terms), so the traditional price increase of the SSNIP test cannot be simulated, as price equals zero. For this reason, different techniques are used to define the relevant market, some of them utilizing machine learning (Decarolis and Rovigatti (2019)).

While the hypothetical monopolist test is not free of uncertainties and difficulties and has been questioned by various experts, it is usually of great utility for competition agencies, given the available evidence, and can also be informative as a starting point for a more detailed investigation.

Often, information on own-price and cross-price elasticities of demand is difficult to obtain or complex to determine. Over the years, several authors have proposed alternative approaches to defining the relevant market.

One alternative approach maintains that products can be considered to belong to the same relevant market if their prices show a certain correlation. This approach examines the extent to which the relative prices of products change over time. A high degree of price correlation indicates that the products belong to the same market, as an increase in the price of one product would trigger demand substitution, which in turn would increase the price of the substitute, leaving the relative price of the two products unchanged. Katsoulacos et al. use a comprehensive set of alternative quantitative tests to delineate a relevant market.

Sometimes, consumers may be unable to react to a price increase; however, producers can do so —for example, by increasing their supply to satisfy the demand of these consumers or by reorganizing their production to produce the product that increased in price. Said augmented level of supply can make the attempted price hike unprofitable.

Competition agencies and courts also take these supply substitution forces into account when defining relevant markets. Even when a hypothetical monopolist does not find a SSNIP profitable considering demand substitution alone, the market may be expanded in terms of products or location after considering the incentives for outside sellers to start producing and selling within the candidate market.

However, there is no consensus regarding at which stage of the analysis process it is best to account for supply substitution, and different criteria exist in the European Union and the United States.

Furthermore, difficulties arise when determining where the limit lies for what is considered a substitute on the supply side. F.M. Scherer notes that the line must be such that it allows the inclusion of only those potential areas of supply with installed capacity, that is, without requiring new investment in plants, equipment, etc. Otherwise, supply considerations would have to be part of the analysis of entry conditions or barriers to entry rather than the definition of the relevant market itself.

When defining the relevant market, the geographic dimension must also be considered, as it can limit the willingness or ability of consumers to substitute products, or the willingness or ability of a supplier to serve consumers. The same firm can operate in several different geographic markets.

In short, to determine the geographic market of a product or service, the researcher asks the following: if the price of a product in area A changes, is the demand in area B affected? If demand in area B is strongly affected, then both sectors should be considered parts of the same relevant geographic market.

The hypothetical monopolist test is also used to define the geographic market. The geographic market will be that in which a hypothetical monopolist of a geographic zone is capable of profitably imposing a small but significant permanent price increase, keeping constant the terms of sale of all products produced in other locations.

This analysis assumes that geographic price discrimination —that is, charging different prices for the same product to buyers in different areas, after subtracting transport costs— would not be profitable for a hypothetical monopolist.

However, if a hypothetical monopolist can identify and set different prices for buyers in certain areas, and these buyers cannot circumvent the price increase by purchasing from more distant sellers, and if other buyers cannot purchase the relevant product and resell it to those facing the higher price (arbitrage), then a hypothetical monopolist could profitably impose a discriminatory price increase. This holds true even when a general price increase would trigger such significant substitution as to be unprofitable (Horizontal Merger Guidelines, 2010).

Another alternative for defining the relevant geographic market is the Elzinga-Hogarty test (1973). Its authors proposed that a given area would be a separate geographic market if it receives few imports and makes few exports. In the words of economists, “Little Comes From Outside” (LOFO) and “Little Out from Inside” (LOFI) (more details in section 4.3).

Typically, the application of the Elzinga and Hogarty test is carried out through trade data and travel patterns between regions, and it was widely used in the United States for hospital merger cases. An example is the case Federal Trade Commission v. Tenet Healthcare Corp (1999), in which the question at hand was whether hospitals had the power to attract patients from distant locations, defining a broad geographic market.

Despite the above, North American jurisprudence has made it clear that one must be cautious with the use of the Elzinga and Hogarty test when defining the geographic market (FTC, 2004). While this test can be useful as a starting point, or to verify the robustness of the chosen definition, it has deficiencies that position it more as a complement than as the main driver of the geographic market definition (Davis and Garcés, 2010).

The use of the Elzinga and Hogarty test lost prominence because, between the years 1994 and 2000, out of a total of 900 hospital mergers, the authorities only challenged 7 of them, losing all 7 (all were approved). This occurred because, most of the time, the competition authorities or courts in charge of overseeing these cases accepted the application of the Elzinga-Hogarty test proposed by the merging parties, which tended to underestimate the impact of the merger on competition.

Thus, as previously seen, the definition of geographic markets can be complicated and data-intensive due to factors such as transport costs, language, regulations, tariff and non-tariff trade barriers, reputation, and service availability.

However, once a competition authority has such inputs, it can opt for different methods to determine the relevant geographic market. Broadly speaking, a regulator could define the market in a global, international, national, regional, or local manner. Typically, all those specifications are defined using pre-existing geographic dimensions. However, in some cases —especially those analyzed with a local focus— the antitrust authority may choose to create a specific geographic dimension. This dimension responds to the concept of isochrones, a concept which will be explained in depth in what follows.

In the past, geographic markets used to be delineated by drawing circles of different sizes around the areas where key inputs were distributed or around relevant urban settlements. Drawing circles arbitrarily may seem unsophisticated; however, it laid the intuition for what would later be known as isochrones.

An isochrone is a line that groups together all locations that can be reached within a constant travel time from a specific starting point. Currently, due to technological advances in software, more coherent geographic markets can be delineated than in the past, taking into account route characteristics and travel speeds in the different zones being evaluated. Consequently, the market layout does not result in a perfect circle but rather features many irregularities arising from the aforementioned particularities (Niels, Jenkins, and Kavangh, 2016).

Technology has allowed the “shape” of the geographic market —delimited by the isochrone— to stop being arbitrary. However, the use of isochrones remains subject to a degree of arbitrariness stemming from the travel time used to delimit the market. Is a 5-minute isochrone more appropriate than one of 10 or 20 minutes?

The answer to this is not obvious and will certainly depend on the specificities of each case. Despite this, to determine the relevant travel time, antitrust authorities use data from various sources to reduce the arbitrariness of their choice. Along these lines, they conduct surveys, obtain information on transport costs, or any other evidence indicative of consumer travel patterns. Nevertheless, given that authorities still have the duty to exercise judgment regarding the relevant time, it is always possible—and useful—to verify the sensitivity of the results by subtly increasing or decreasing the time used.

How is the starting point of the isochrone defined? In the logic of the hypothetical monopolist test, the “center” of the isochrone should reflect the “focal product” as accurately as possible. An example of this can be seen in the fictitious case analyzed by Niels, Jenkins, and Kavanagh (2016), where the focal product was defined based on one of the cinemas of chain “A.”

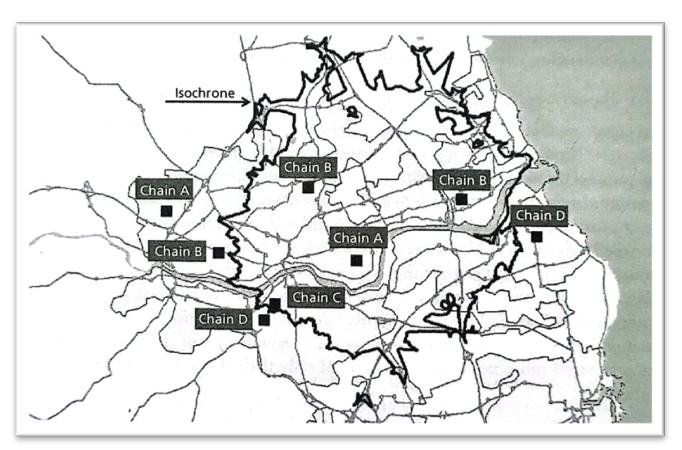

Figure 1: 20-minute isochrone for cinema chains in a fictitious city

Source: Niels, Jenkins y Kavanagh (2016)

In the figure, four cinema chains compete in the city: Chain “A”, which has 2 locations; Chain “B”, with 3; Chain “C”, with 1 location; and Chain “D”, with 2 locations. The demarcated area corresponds to the 20-minute isochrone relative to the Chain “A” cinema (located in the center). Its irregular shape responds —as previously anticipated— to speed, the road network, and the possibility for potential customers to access the specific product.

If the fictitious regulator in the previous case considered the 20-minute isochrone as the relevant geographic market, competition would occur between Chain A’s central location, two Chain B locations, and one Chain C location. In contrast, if the geographic market were defined by the city’s total area, operator D—with two locations—would also be a competitor; furthermore, the analysis would have to include two additional branches, one for Chain A and another for Chain B.

If it is assumed that the regulator’s final decision considers the 20-minute isochrone as the relevant geographic market, then it is possible to point out that, since Chain “D” has no presence within the isochrone, operator “D” exerts no competitive pressure on Chain “A”.

The previous isochrone is supply-centered, as it focuses on the distribution of the product. As observed, the isochrone was constructed with respect to the place where the service is offered, and not with respect to the position of the customer, who is the one demanding it. Competition between cinemas does not occur merely because they are 20 minutes apart (supply perspective); rather, it occurs because both are within reach of the same consumers (demand perspective). For this reason, supply-based isochrones may not represent the relevant geographic market with total precision.

Another approach applied is to recenter the isochrones based on major population centers (instead of the sellers’ locations) to evaluate which points of sale are accessible to consumers. A purely theoretical angle would suggest doing this for every consumer; however, given data constraints and the complexity of the process, it is preferable to consider only the main population centers. In fact, in practice, it is frequent for antitrust regulators to adopt the supply-based approach for simplicity.

In Chile, for example, in the SMU/Inmobiliaria Santander merger, the National Economic Prosecutor’s Office (FNE) used 5- to 15-minute travel isochrones for supermarket locations (providing a conservative view and a less restrictive one, respectively) around a list of locations belonging to the merging parties (supply-side approach). These locations had the particularity of being in areas sufficiently remote from one another (different communes and regions), such that each isochrone was part of a different relevant market (for more information on this case, you can review our CeCo note: Unimarc/Montserrat Operation: FNE and TDLC give green light in parallel).

In any case, the use of isochrones is not limited to supermarket cases. In practice, this way of delimiting the geographic market can be useful for practically any case where local market analysis is sought. For example, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) in the United Kingdom has employed isochrones for mergers related to betting shops, cinemas, bookstores, and DIY (home improvement) stores, to name a few (Desai, 2008). Thus, isochrones constitute a versatile way to fix the relevant geographic market in local contexts when data on consumer travel or preferences in the sector is available.

In competition analysis, a fundamental initial stage for measuring the extent of market power consists of defining the relevant market. This initial stage has significant repercussions on the subsequent analysis of anticompetitive conduct, and as such, the outcome of many (antitrust) cases has turned more on the definition of the market than on any other substantive issue (Baker, 2007).

In 1997, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) decided to challenge in court the Staples and Office Depot merger, the two main office supply stores in the country. The definition of the relevant market was a crucial aspect of the district court’s resolution.

The U.S. agency claimed that the relevant product market consisted of the sale of consumable office supplies through office supply superstores. Under this definition, the FTC did not include products such as computers, fax machines, other office machines, and furniture, but only products such as paper, pencils, file folders, post-its, and floppy disks.

For their part, the defendant companies argued that this definition was too “narrow” and that the definition of the relevant market should include all office products, of which the merged entity only possessed 5.5% of total sales in the United States. Regarding the geographic market, there was consensus that it covered all areas of the states in which both companies had stores.

To defend its case, the FTC presented evidence showing that Staples’ prices were 13% higher in locations where it did not compete with Office Depot and OfficeMax than in those where it did. Additionally, Office Depot’s prices were 5% higher in the same scenario.

This evidence had a great impact in the Court’s decision, as it could be concluded that the defendant companies did not consider other stores that might sell office supplies —such as Wal-Mart, Kmart, or Target— as competitors for their products. These did not exert sufficient competitive pressure on the defendants to prevent a price hike.

In contrast, Staples, Office Depot, and OfficeMax competed so closely that office superstores were considered a separate market from general office supply retailers.

The fact that a small but significant increase in Staples’ prices did not trigger substitution toward other office supply retailers provided sufficient evidence of low cross-price elasticity. This demonstrated that the defendants operated in a distinct market, leading the district court to halt the merger.

This case introduced complex econometric studies on price changes as part of the evidence for defining the relevant market. Since then, both companies and competition agencies have used direct evidence obtained from the closest competitors to define the market and the effects a merger might have on prices and/or consumer welfare.

Furthermore, antitrust bodies had traditionally focused on the increased probability of collusion following a merger as the main theoretical basis for blocking it. In contrast, this case focused on the possibility of a merger having “unilateral effects,” such as price increases.

For a detailed analysis of the case, see Dalkir and Warren-Boulton (2004).

On June 20, 2008, the National Economic Prosecutor’s Office (FNE) and the company Comercial Canadá Chemicals S.A. filed a lawsuit before the Court for the Defense of Free Competition (TDLC) against Compañía Chilena de Fósforos (CCF) for exclusionary abuse of a dominant position. In this case, there was an intense debate surrounding the definition of the relevant market.

On one hand, the FNE claimed that the relevant market corresponded to the market for safety matches sold in Chile. This definition excluded lighters, as the FNE asserted that lighters were used almost exclusively for cigarettes, while matches were used for household appliances; therefore, they were not close substitutes.

According to the FNE, the fact that matches are primarily sold in supermarkets while lighters are sold in small convenience stores reinforced the case for leaving lighters out of the relevant market. Furthermore, the “value per light” of matches is approximately 1000% higher than that of lighters.

In contrast, CCF argued that matches were indeed sold to smokers in small businesses. Additionally, they argued that large matches —ideal for household use and only for that purpose— represented only 20% of the company’s sales, noting that if matches were used only for domestic purposes, this number would be higher. They also pointed out that the entry of lighters coincided with the decline of the matchstick industry, which would indicate substitution. For the defendant, it was a single “ignition market” that included matches and lighters equally.

CCF’s market share —and the resulting market power— changed drastically depending on the definition.

Ultimately, the TDLC agreed with the FNE and defined the market as the market for matches within Chilean territory, given that there was no significant substitution between matches and lighters that would allow for the inclusion of both.

The TDLC considered that a fundamental piece of evidence to determine the degree of substitution between both products was the econometric estimation of matchstick demand in Chile and how it was exogenously affected by the price of lighters, which had been presented in a CCF report. The estimated correlation between the sale of matches and lighters in Chile was -0.72, which, according to the court, did not ensure that both products were good enough substitutes to belong to the same relevant market.

The fact that the products were sold in different locations also contributed to this decision —matches were sold in supermarkets and lighters in smaller shops— as confirmed by information provided by various retail actors, among other informants.

The TDLC concluded that CCF did have a dominant position because, among other reasons, it held approximately 80% of the total relevant market share and was the only producer of matches in Chile.

In 1994, the United States challenged the merger of Mercy Health Services and Finley Tri-States Health Group, who had agreed to associate their hospitals in Dubuque, Iowa. Both medical facilities were the only ones offering acute care (the relevant product market) in that locality (despite the existence of other rural facilities in the surrounding areas). While there were several regional hospitals providing the same services as Mercy and Finley, they were located between 70 and 100 miles from Dubuque, making the merger complicated, particularly regarding its relevant geographic market definition.

The government argued that the geographic market included Dubuque County and a semicircle with a radius of 15 miles, extending from the eastern edge of Dubuque into Illinois and Wisconsin. This definition positioned Mercy, Finley, and Galena-Stauss Hospital as competitors. Eighty-eight percent of patients originating from this demarcated zone used one of the three mentioned hospitals; only 2% were treated at Galena-Stauss, while the rest were treated at Mercy or Finley.

In contrast, the defendants argued that the geographic market consisted of Mercy, Finley, the seven nearest rural hospitals, and the regional hospitals located in Cedar Rapids, Waterloo, Iowa City, Davenport, and Madison. Under this definition, Mercy and Finley hospitals only treated 10% of the patients present in that area.

The United States defended its definition based on the opinions of primary healthcare consumers in Dubuque, information regarding the most desirable locations for physicians to practice, physician opinions, and patient flow data. Based on this, the government concluded that Mercy and Finley patients could not switch to a rural hospital due to loyalty to their physicians. Furthermore, it was determined that doctors considered Mercy and Finley to be comparable hospitals and were willing to work at both. Under the U.S. government’s defense, rural hospitals would not exert competitive pressure on Mercy and Finley.

To verify that the geographic market was limited, the government employed the Elzinga-Hogarty test. This test analyzes empirical data by calculating two distinct ratios: (1) the LIFO (Little In From Outside) percentage, calculated by dividing the number of local residents treated at area hospitals by the total number of patients those hospitals see; and (2) the LOFI (Little Out From Inside) percentage, calculated by dividing the number of residents who stay within the area for care by the total number of residents in that area who require hospitalization. On the one hand, the LIFO measures how “local” a hospital’s business is. It asks: Of all the people sitting in our waiting room right now, how many actually live in this neighborhood? If LIFO is high (90%), it means the hospital isn’t a “destination” for outsiders; it primarily serves the immediate area. On the other hand, LOFI measures how “loyal” (or stuck) the local residents are. It asks: Of all the people who live in this neighborhood and need a doctor, how many stayed here instead of driving to the next town? If LOFI is high (90%), it means the residents aren’t leaving; they view the local hospitals as their only practical option. When both calculations result in a figure of 90% or higher, the market definition is said to be “strong.” Conversely, if the numbers are at 75%, the market definition is considered “weak.”

The geographic market definition suggested by the government met the “weak” threshold, as 76% of inpatients at Mercy or Finley came from this geographic area, while 88% of those residing in the stipulated area were treated there. Increasing the radius from 15 to 35 miles around Dubuque allowed for a “strong” definition. According to the government, even then, the regional hospitals (which also provided acute care) remained outside the market and could only compete for patients at the margins.

However, the defendants strongly criticized the market definition proposed by the government, as it relied on incorrect assumptions, namely: i) that patients were loyal enough to their doctors not to switch to another hospital; ii) that they would be unwilling to travel long distances to go to another medical facility; and iii) that current patient “exports” and “imports” were a good approximation of product substitutability from a demand perspective.

Additionally, Mercy and Finley hospitals maintained that the government’s argument relied too heavily on past market characteristics without considering current market trends. Likewise, they suggested that a 5% price increase by the merged entities would be sufficient for patients to decide to travel to more distant hospitals for care.

Ultimately, the government’s excessive reliance on the Elzinga-Hogarty test proved counterproductive, as the court noted that the government failed to establish an adequate relevant geographic market. In its ruling, the court agreed with the defense of Mercy and Finley, stating that the government made invalid assumptions and failed to analyze the case with a dynamic approach, opting instead for a static approach based on past events. Consequently, the court stated that it could not be sustained that the Mercy/Finley merger would have anticompetitive effects and, therefore, ruled in favor of the defendants.

Market definition is not essential for all antitrust cases, in part due to the emergence of new methodologies. There are also those who consider that defining the relevant market is impossible and that attempting to define it is counterproductive, suggesting that this methodology should be abandoned.

Farrell and Shapiro (2010) developed an initial indicator to determine if a proposed merger between competitors in a differentiated product industry might raise prices through unilateral effects.

This indicator measures the upward pricing pressure resulting from the merger, which requires comparing two opposing forces: the loss of direct competition between the merging parties, which creates upward pressure on prices, and the marginal cost savings from the merger, which creates (compensatory) downward pressure on prices. If the net effect of these two forces creates upward pressure on prices, the merger should be subjected to further scrutiny.

This measurement, established in the practice of competition agencies, is based on the price/cost margins of the merging firms’ products and the degree of direct substitution between them. According to the authors, this approach is practical, more transparent, and better grounded in economics than methods based on market concentration.

In competition law, the market definition/market share paradigm —under which a relevant market is defined and relevant market shares within it are examined to then draw inferences about market power— has generated deep discussion among experts. This discussion contrasts the opinions of Harvard professor Louis Kaplow and former DOJ official Gregory J. Werden.

In his provocative essay “Why (ever) define markets?” (2010), Kaplow argued that the process of market definition is incoherent from the standpoint of basic economic principles and should therefore be completely abandoned.

His main argument is the impossibility of determining the best market definition without already having a bias toward an optimal estimate of market power. It would be a circular and tautological exercise, rendering subsequent analysis useless and possibly leading to erroneous results.

According to Kaplow, in practice, to determine whether market definition A involves fewer errors than market definition B, it is necessary to have an opinion on the magnitude of these errors. Now, these errors consist of the deviation between the inference of market power derived under one market definition or another and one’s own best estimate of actual market power. “Therefore, evaluating errors, necessary to choose the relevant market, presupposes that one has already formulated their best estimate. Thus, defining markets is useless.”

In response, Gregory Werden published “Why (ever) define market: An answer to Professor Kaplow” in defense of the tool. In his article, he states bluntly: “market delineation serves purposes that Professor Kaplow overlooks, does not require a prior assessment of market power, and cannot be abandoned.”

According to Werden, market delineation is necessary to examine issues such as barriers to entry and the durability of market power, not just market shares. Furthermore, he asserts that the method proposed by Kaplow for assessing market power without previously defining the relevant market does not work when that power derives from the sale of multiple substitute goods.

Werden considers that, although the tools of modern economics often allow for reliable quantitative analysis —such as the evaluation of probable competitive effects of horizontal mergers— these tools must be supplemented by market delineation.

In the digital economy, markets have emerged where goods or services are offered for free (in monetary terms), especially in multi-sided platforms such as search engines and social networks that connect interdependent user groups. In these cases, what the consumer/user gives in exchange for use of the service generally is his or her personal (and non-personal) data, or simply their attention.

Traditional tools for defining the relevant market, such as the SSNIP test, are not applicable when the initial price is zero, as price increases cannot be performed nor can changes in consumer behavior be observed. This makes it difficult to evaluate demand substitution and delimit precisely the market using conventional methods, leading to the need for alternative methodologies (O’Donoghue and Padilla, 2020).

One of the main proposals to replace the SSNIP test with the SSNDQ test, which is an adaptation of the SSNIP test approach. Instead of analyzing price increases, this test examines whether a significant and non-transitory reduction in the quality of a service leads users to opt for substitute alternatives. Some key aspects of quality that are considered include user experience, security, and privacy, among others (Mandrescu, 2018).

For example, one can hypothesize a 25% decrease in the quality of a search engine. If this degradation motivates consumers to switch providers, the relevant market is delimited based on the sensitivity of users to such changes in quality.

However, proponents of the SSNDQ test acknowledge that its practical application faces significant challenges. This is due to the difficulties in accurately defining and measuring the quality of the good or service, which limits the use of this tool. Indeed, the advantage of the SSNIP test is its mathematical operability made possible by price valuation (OECD, 2013).

Silva (2024) reviews other tools for defining the relevant market in zero-price contexts. One of them is the SSNIC test. This test analyzes how consumers would react to a 5% to 10% increase in non-monetary costs. If this change induces users to migrate to other products, the relevant market can be delimited based on their sensitivity to these costs (Newman, 2016).

On the other hand, there is the A-SSNIP test proposal, based on the idea that in zero-price markets, the real “price” is the user’s attention. This tool, applied to social media platforms, evaluates how consumers would react to a small but significant and non-transitory increases in unwanted messages or advertising load (see CeCo note on the “attention market”). By focusing on attention as a valuable resource, this method allows for the analysis of demand substitution and defines the relevant market by considering the sensitivity of users to changes in this “attentional price” (Wu, 2019).

Desai, K. (2008). Isochrones: Analysis of Local Geographic Markets. Mayer Brown.

Kaplow, L. (2010). Why (ever) Define Markets?. Harvard Law Review, 437-517.

Niels, G., Jenkins, H., & Kavanagh, J. (2016). Economics for Competition Lawyers.

Simon, B., & Darcey, M. (1995). A Relevant Market Is Something Worth Monopolising. Unpublished Mimeo.

United States v. E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 351 U.S. 377 (1956).

Wu, T. (2019). Blind Spot: The Attention Economy and the Law. Antitrust Law Journal, 82(3), 797.

** El glosario original fue modificado originalmente con fecha 23 de noviembre de 2022, agregando la sección 3.1 “Isócronas” y la sección 4.3 “EE. UU: Caso Mercy Health Services/ Finley Tri-States Health Group”. Luego, fue modificado el 10 de febrero agregando la sección 6 “Desafíos en la definición del mercado relevante con bienes de precio cero”, incluyendo las subsecciones 6.1 “Small but Significant Non-Transitory Decrease in Quality (SSNDQ)” y 6.2 “Otras herramientas propuestas”.