Newsletter

Suscríbete a nuestro Newsletter y entérate de las últimas novedades.

https://centrocompetencia.com/wp-content/themes/Ceco

volver

Classical economic theory predicts that in a perfectly competitive economic system without direct government intervention, the individual actions of people and firms pursuing their own self-interest inadvertently contribute to the general welfare of society. According to this line of thought, a market economy should, by itself, allocate the available resources efficiently, achieving what is known as “competitive equilibrium.”

Market failures are defined as circumstances or factors that prevent markets from allocating resources efficiently, challenging the assumptions underlying competitive equilibrium, such as perfect competition, absence of externalities, or perfect information.

In what follows, the main categories of market failures are reviewed: (i) externalities, (ii) public goods and common resources, (iii) market power, and (iv) asymmetric information.

An externality occurs when the purchasing and selling decisions of a product or service affect the welfare of a third party, who is neither paid nor compensated for that effect (Mankiw, 2012). In these cases, market prices do not reflect the side effects associated with the production or consumption of these goods, so that the competitive equilibrium is not efficient for society as a whole.

A negative externality refers to situations in which an economic activity reduces the welfare of individuals who are not part of the market, without those individuals being compensated for the harm they receive. This type of externality may arise from both the production and the consumption of a good or service.

For example, a factory that emits pollutants into the air or water as part of its production process affects the health of the population living nearby. If the producer makes decisions based solely on the direct production cost it faces (the firm’s private cost) and its possible income —ignoring the social cost of pollution— the market equilibrium will be unable to maximize total benefit for society. Similarly, but from the consumption side, when a person smokes a cigarette, they not only put their own health at risk, but also those around them who inhale the smoke released by the cigarette (passive smokers).

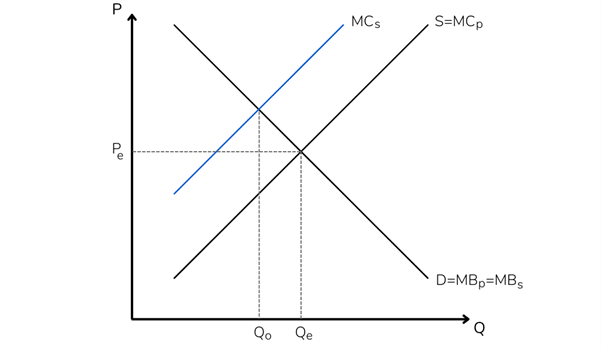

Graphically, the equilibrium of a market with negative externalities takes the following form:

Graph No. 1: Market equilibrium with negative externalities

Own elaboration

In this context, the marginal social cost (“MC s” in Graph No. 1), defined as the cost incurred by society for the production of one additional unit of the good, is higher than the private marginal cost (“MC p”), defined as the cost to producers of manufacturing one additional unit of the good (aggregate supply of the market in question).

This difference between social and private marginal cost arises because producers do not internalize the negative impact that their production has on the rest of the population. If these effects were considered, costs would increase, causing the quantity produced to fall and reach the socially optimal level (“Qo”), which is lower than the quantity at competitive equilibrium (where only the firm’s private costs are considered), “Qe.” The same logic applies to cases in which negative externalities arise in consumption (there is more consumption than what is socially optimal).

Positive externalities, unlike the previous case, occur when the production or marketing of a good or service increases the welfare of third parties, without them having to pay for such a benefit. Again, these may arise from either the production or the consumption of a product.

Suppose, for example, that a firm allocates economic resources to research and development of new products. When this occurs, the firm has the potential to foster greater competition and raise people’s quality of life by providing more effective and convenient solutions. That is, the benefits may extend beyond the firm itself. In the same way, when a person is educated, their productivity increases and they can earn higher wages. In addition to these private benefits, the rest of society also benefits from having a more informed and productive citizen.

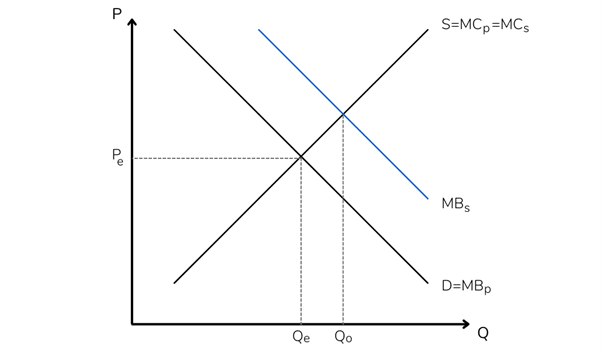

Graphically, the equilibrium of a market with positive consumption externalities takes the following form:

Graph No. 2: Market equilibrium with positive externalities

Own elaboration

In this case, the marginal social benefit (“MB s” in Graph No. 2), understood as the benefit obtained by society from one additional unit of the good, is higher than the private marginal benefit (“MB p”), corresponding to the benefit obtained by the consumer from this good (aggregate demand of the market in question).

The difference between social and private marginal benefit arises because consumers do not internalize the benefit that their consumption generates for other people (they only take into account the private benefit they obtain from this consumption). If that were not the case, the quantity consumed would increase, reaching the socially optimal level (“Qo”), which is higher than the quantity at competitive equilibrium, “Qe.” The results are analogous for cases in which positive externalities arise in production (less is produced than is socially optimal).

As we have seen, in the absence of regulations or public policies that enable agents to internalize the effects of their actions on third parties, externalities lead to inefficient market allocations, either because more than the socially optimal amount is produced or consumed (negative externality), or less (positive externality).

Broadly speaking, there are two types of solutions to address these problems and restore greater economic efficiency: public solutions and private solutions.

Public solutions are those measures implemented by governments or other regulatory institutions. Following Samuelson (2009), this type of solution can be classified along two dimensions: direct or indirect.

Direct controls refer to explicit interventions by the government or public institutions to regulate a market and thus correct a given externality. An example of this is a law establishing maximum level of emissions for an industry, seeking to align with the socially optimal production levels.

Indirect controls, by contrast, are based on market-oriented solutions. For example, the authority may establish corrective taxes or subsidies to align private incentives with socially optimal levels. In other words, a corrective tax imposes a monetary cost on the generation of a negative externality, forcing the agent to incorporate it into its activity; whereas a corrective subsidy rewards the generation of positive externalities, encouraging agents to produce them to a greater extent.

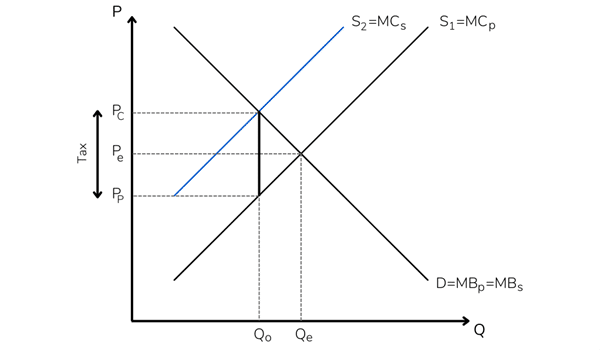

Specifically, in a market equilibrium with negative production externalities, such as the one illustrated in Graph No. 1, a corrective tax can be applied in the following way:

Graph No. 3: Application of a corrective tax

Own elaboration

This tax imposes a monetary charge proportional to the quantity produced, to make the producer internalize the social cost generated by its production. As a result, for every level of production (values on the horizontal axis), the production costs faced by the firm increase. Thus, the relevant supply faced by the producer is no longer “MC p” but “MC s” (Graph No. 3).

Under this new cost structure, the producer optimizes its production by equating its new supply curve (“S2”) with demand (“D”), reaching a new market equilibrium. The idea is that the magnitude of the corrective tax should be such that, under the new supply curve, the producer maximizes its profit at the same level at which social welfare is maximized (“Qo”). This is what is known as the “optimal corrective tax.”

In Graph No. 3, the value of this tax (under which the socially optimal quantity is produced) corresponds to the difference between two prices: the price charged by the producer when it internalizes the externality (“PC”), and the price it would charge for producing the socially optimal quantity (“Qo”) in the absence of the tax (“PP”). These types of taxes are known as Pigouvian taxes, in honor of the British economist Arthur Pigou, who first developed this method for the control of externalities in the 1920s (Parkin, 2009).

The logic for a corrective subsidy in a market with positive externalities is analogous to that of the corrective tax, with the difference that, in this case, the subsidized amount is that which reduces the firm’s production costs by such an amount that it increases its production until it reaches the socially optimal level. In both cases, the economic incentives of the agents themselves are what allow the “private” competitive equilibrium to converge to the socially optimal equilibrium.

Other economic measures, such as the implementation of tradable pollution permits, can yield similar results.

Even without government or regulatory intervention, the effects of some externalities can be offset through actions taken by individuals and firms. These measures are known as private solutions.

On the one hand, social sanctions and moral codes can bring private behavior closer to the social optimum (Mankiw, 2012). People avoid engaging in harmful practices, such as throwing garbage in public spaces, out of empathy for others or due to the bad reputation such actions generate. Similarly, some firms may commit to social causes, such as environmental protection, to build a good image and avoid community criticism.

Likewise, legal liability rules make agents more aware of the side effects associated with their consumption or production patterns. For example, in most legal systems, when a person is injured or becomes ill from using a defective product, the manufacturing firm is legally liable for the damage caused. This makes the firm internalize the externality and consider some of the social costs of its production.

A generalization of this type of solution is the Coase Theorem, proposed by the British economist Ronald Coase in 1960, which holds that the parties involved in an externality can reach an efficient solution without the need for government intervention, under certain conditions. In particular, that property rights are well defined, transaction costs are low, and there are few affected parties. Despite the valuable conceptual basis it provides, the Coase Theorem is difficult to apply in practice due to the multiple assumptions it involves.

To understand public goods and common resources, it is necessary to grasp two essential concepts: rivalry and excludability.

According to Parkin (2009), defines a rival good as one whose by an individual diminishes the quantity available for others. In contrast, a good is excludable when access can be restricted to only those who pay for it; that is, when it is possible to prevent a person from using the good.

These two properties (rivalry and excludability) give rise to four types of goods: private goods, club goods, common resources, and public goods.

Tabla N°1: Types of goods

| Rival | Non-rival | |

|---|---|---|

| Excludable | Private goods | Club goods |

| Non-excludable | Common resources | Public goods |

Own ellaboration

Private goods are those that are both excludable and rival. These are the typical goods and services of traditional markets, such as food, cars, and clothing items. Thus, for example, when a person buys an ice cream, they reduce the number of ice creams available for sale. At the same time, only the person who buys an ice cream benefits from its consumption.

There are also goods that are excludable but non-rival, known as club goods. Water and electricity supplies, private parks, and cable television are examples of this type of good (consuming electricity does not prevent other people from consuming it, but each agent must pay to benefit from it).

Typically, this type of good is supplied by natural monopolies. In such industries, the most efficient way to produce a product —the one that minimizes production costs— is that in which a single firm is responsible for the entire process.

By contrast, the market has difficulties supplying markets for non-excludable goods, such as public goods and common resources.

A public good is characterized by being non-excludable and non-rival. This means that everyone can consume it simultaneously, and no one can be prevented from enjoying its benefits. Examples of this type of good include public lighting, national defense, and public spaces.

From the demand side for these goods, consumers are incentivized to act as “parasites”, “stowaways” or “free riders”. A free rider is a person who can obtain the benefits of a public good without having to pay for it. This situation reduces the incentives of private economic agents to participate in the provision of these goods (they cannot charge for the service they provide). As a result, the private supply of public goods is scarce, and the competitive equilibrium is unable to deliver the socially optimal quantity of these goods, generating underproduction.

In practice, governments and other public institutions take on the task of supplying most public goods, using resources obtained from taxes and other public revenue sources.

A common resource is a good that is rival and non-excludable: although one person’s consumption reduces the quantity available for others, no one can be prevented from using what is available. Fish in the ocean, green areas, and congested streets are some examples of common resources.

Since no charge is made for their consumption, people tend to overuse this type of good. The absence of incentives to prevent overexploitation and depletion of common resources is known as the “tragedy of the commons.” For these reasons, since a situation of competitive equilibrium does not allocate common resources efficiently, overproduction or overexploitation arises.

Correcting this market failure requires the implementation of regulations, such as the establishment of property rights or production quotas.

One of the main assumptions of competitive equilibrium is that there is perfect competition among producers in a market. Hence, the equilibrium price is set at the level of firms’ marginal cost (price = marginal cost).

However, in practice, we should expect all firms to have some degree of market power, defined as the ability of companies to profitably raise prices above their marginal costs (European Comission, 2002).

The exercise of market power constitutes a market failure because it entails a loss of efficiency, which in turn implies a loss of social welfare. The higher the price set, the greater the welfare loss caused by market power.

Competition law’s institutional framework is responsible for preventing and controlling the exercise of abusive market power, as well as ensuring that markets remain competitive.

Perfect information is another recurring assumption in classical economic models. This principle assumes that all market participants have access to all relevant information about the prices, quality, and quantities of the goods and services traded.

In real life, it is common for some actors to possess more information than others. This situation, called information asymmetry, can lead to inefficient market outcomes, such as underproduction or reduced product quality.

Some of the best-known market failures generated by information asymmetries are moral hazard and adverse selection.

Moral hazard is the tendency of a person, who is being monitored imperfectly, to behave in a dishonest or undesirable manner (Mankiw, 2012). Adverse selection, on the other hand, is the tendency of a person to enter into contracts in which they use their private information to their own advantage and to the detriment of the less informed party (Parkin, 2009).

To illustrate, consider the market for auto insurance. An auto insurance policy is a contract between an insurance company and the owner of a vehicle. If the car is involved in a crash, damaged, or stolen, the company undertakes to cover all or part of the financial losses associated with these unforeseen events.

Asymmetric information in this market lies in the fact that individuals have more detailed and accurate information about their own risk of being involved in an automobile accident than insurance companies do. The latter can only assess, imperfectly, the risk of their potential clients by reviewing their driving records and other types of records.

On the one hand, moral hazard predicts that people will behave in a riskier manner after purchasing insurance, because they know that they will not have to bear all the costs in the event of an accident. This behavior is undesirable for insurance companies, which expect reasonable behavior from their clients.

On the other hand, adverse selection refers to the fact that people at higher risk of having accidents are more likely to purchase insurance than lower-risk drivers. This can lead to an imbalance in the insured population, with a higher proportion of high-risk drivers in the pool of policyholders, something that clearly disadvantages insurance companies, which have less information than their clients.

The combination of these phenomena —a more reckless behavior and a higher proportion of risky clients— can lead to an increase in reported accidents and, therefore, an increase in costs for insurance companies in the long run. As a result, equilibrium prices will be higher than those that would exist in a market with perfect information.

In conclusion, competitive equilibrium differs from the social optimum in a market with asymmetrical information. To mitigate these effects, measures must be adopted that promote greater transparency and monitoring, as well as other actions specific to each market —for example, the inclusion of deductibles and clauses in insurance contracts.

Mankiw, N. G. (2012). Principles of Economics (6th ed.). Harcourt College Publishers.

Parkin, M. (2009). Economics (8th ed.). Addison-Wesley Inc., Reading, Massachusetts.

Samuelson, P. & Nordhaus, W. (2009). Economics (19th ed.).

*Este glosario fue editado el 6 de junio de 2024.