Newsletter

Suscríbete a nuestro Newsletter y entérate de las últimas novedades.

https://centrocompetencia.com/wp-content/themes/Ceco

volver

The term efficiency has several uses. In the context of industrial organization, competition law and competition policy, it is related to the most effective way of using scarce resources.

Generally, two types of efficiency are distinguished: technological (or technical) and economic (or allocative). A firm may be more technologically efficient than another if it achieves the same level of output with fewer physical inputs. Economic efficiency refers to instances in which inputs are used in such a way that a given level of output is achieved at the lowest possible cost. An increase in efficiency occurs when a given level of output, or output on a larger scale, is achieved at a lower cost (OECD, 1993).

Economists generally consider that competition leads individual firms or economic agents to act efficiently. Efficiency increases the likelihood of business survival and success and the likelihood that scarce economic resources will be used to the fullest. At the firm level, efficiency arises mainly through economies of scale and scope and, over a longer period, through technological change and innovation.

The sources of efficiency examined in the analysis of economic welfare are static (allocative and productive) or dynamic. Typically, the underlying tension in competition policy is, on the one hand, between allocative efficiency versus productive efficiency and, on the other hand, between static efficiency versus dynamic efficiency.

One fundamental rationale for mergers is the possibility to achieve efficiency gains. Therefore, sometimes merger analysis addresses the productive and/or dynamic efficiencies of a transaction. In turn, practices examined as potential instances of abuse of a dominant position, although potentially exclusionary, may also have efficiency benefits (for example, tying or bundling practices).

Competition is a process that forces firms to become efficient and offer more and more diverse products and services at lower prices. Economic theory teaches that when there is sufficient rivalry and competitive pressure in markets, the result will be that prices are closely aligned with underlying costs, a benefit that is associated with allocative efficiency and that directly benefits consumers.

On the other hand, market power, in addition to causing a welfare loss by allowing prices to be too high, generates other inefficiencies related to the lack of cost reduction, affecting productive efficiency. As will be seen below, market power causes a loss of efficiency (and therefore of welfare) associated with allocative efficiency (high prices) and with productive efficiency (unproductive activities).

Let us first analyze why market power reduces allocative efficiency. We will assume a scenario in which the level of technology (costs) is given, and in which the most efficient technology available is used (these assumptions will be relaxed later when considering dynamic efficiency).

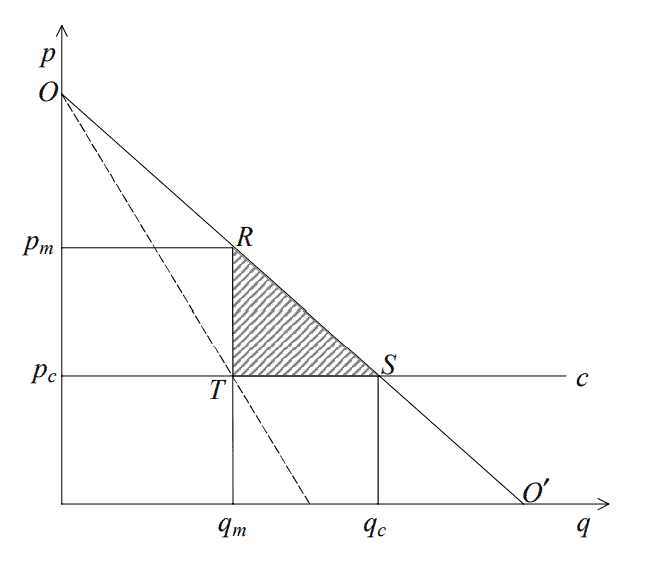

Consider the extreme case in which market power is at its maximum, that is, the industry is monopolized by a single firm that charges the monopoly price. In this scenario, the monopolist has constant marginal costs c and faces a linear demand (OO’). We are interested in the relationship between price and quantity supplied. The following graph illustrates this relationship for a monopolistic market:

Graph 1: Price and output with and without firm market power

We know that market demand (OO’) has a negative slope (the higher the price, the lower the quantity demanded) and that welfare is defined as the sum of consumer surplus (the difference between willingness to pay and the price actually paid) and producer surplus (the difference between the final price and the costs incurred). The graph shows two comparison scenarios: (i) the case of perfect competition, where output is offered at price pc, and (ii) the monopolistic case, where output is offered at price pm.

In the more competitive equilibrium, welfare is given by the triangle OpcS, corresponding to consumer surplus (firms have no surplus, since profits are equal to zero). Under monopoly, welfare is given by the area described by the points OpcTR, being the sum of producer surplus PmPcTR (which this time is positive) and consumer surplus OPmR.

The main point about the allocative inefficiency caused by market power is the following: when prices are above marginal costs, this generates greater producer surplus, but not enough to offset the lower consumer surplus caused by higher prices (Motta, 2004).

The higher the price, the greater the welfare loss caused by market power. This suggests that welfare decreases with market power. In the graph, this loss of social welfare is given by the area of triangle RST, which is a deadweight loss to the economy and is associated with the fact that, at a monopoly price, there is an entire segment of demand that is left empty-handed.

It must also be noted that, compared to monopoly, competition increases net benefit (that is, total social welfare), but to the detriment of producer surplus. This may be trivial, but it illustrates the main interests behind the different situations. Producers in an industry will attempt to lobby for greater protection and less competitive pressure, while consumers will be interested in promoting measures that maximize competition.

Additionally, there is some debate as to the appropriate welfare measure to be applied. Some argue that all decisions should be based solely on avoiding the loss of social welfare (the triangle), which summarizes consumer harm. Others argue that producer surplus must be taken into account because much of it is dissipated in the pursuit of monopolistic profits. This leads to consideration, below, of productive efficiency.

We have seen that a monopolist —or more generally, a firm that enjoys substantial market power— charges a price that is too high and that leads to a welfare loss, which is referred to as allocative inefficiency. However, there could be an additional welfare loss, referred to as productive inefficiency, if a firm operating under monopoly has a higher cost than it would if it operated in more competitive environments.

Under monopoly, the firm has little incentive to be more efficient and to choose technologies that allow it to produce at lower costs. Returning to the previous graph, an increase in the monopolist’s costs (the straight line c) leads to a greater loss in social welfare than in the case where only allocative inefficiency is at play (Motta, 2004). Why does this happen? There are two main arguments suggesting that a monopoly is likely to entail productive inefficiency. First, managers of a monopolistic firm have fewer incentives to exert themselves and to reduce costs. Second, when there is competition, more efficient firms tend to survive and prosper, while less efficient ones end up exiting. If the industry is structured as a monopoly, the market will not operate under a “survival of the fittest” logic and an inefficient firm is just as likely to survive as an efficient one.

The idea that competitive pressure leads a firm to seek the most efficient way to organize its production and reduce its cost is very old. Leibenstein (1966) introduced the concept of “X-inefficiency” to reaffirm the idea that monopolistic power —and the “quiet life” that accompanies it— generates managerial inefficiency. As will be seen, this “managerial slack” is an argument that applies not only to productive inefficiency, but also to dynamic inefficiency: the quiet life does not push managers to innovate either.

So far, the properties of market power that we have reviewed have been static rather than dynamic. On the one hand, market power leads to allocative inefficiency, since a firm (for any given technology) charges a price that is too high. On the other hand, market power also leads to productive inefficiency, since a monopolist might not adopt the most efficient technology available.

Yet, it is also necessary to consider dynamic efficiency, which refers to the extent to which a firm introduces new products or production processes. If static efficiency examines whether competition pushes firms to operate on or closer to the current efficient production frontier, dynamic efficiency considers whether competition pushes firms to move the efficient production frontier faster or further.

A monopolist —or more generally, a firm with market power— may have fewer incentives to innovate, thereby adding dynamic inefficiency to the list of welfare losses created by firms with market power (Motta, 2004). Put simply, the intuition is as follows: competition pushes firms to invest to improve their competitive position vis-à-vis their rivals. The absence of competition reduces this incentive to innovate, and this in turn means that a monopolist will be less efficient (less innovative) than firms that operate under competition.

Despite this, one must not jump to the conclusion that more competition always leads to more innovation. There is a long-standing debate in the economic literature on the link between monopolistic power and innovation. This debate goes back to Schumpeter, who suggested that monopoly power fosters research and development efforts. Indeed, firms’ incentives to innovate are determined not only by the existence of competition but also by the possibility of appropriating the results of their investment. If competition is too intense, appropriability is reduced and the incentive to invest and innovate is also reduced.

Because firms are unlikely to invest without a reasonable expectation of capturing the returns, the prospect of market power is a critical driver of innovation and development.

The balance between ex ante efficiency (preserving firms’ incentives to innovate) and ex post efficiency (ensuring the wide diffusion of innovations once they exist) lies at the heart of public policies on investment and innovation. Patents and other intellectual property rights are a way of allowing appropriability. Thus, a firm knows that, for a certain period, it will be able to fully exploit the results of its innovations.

From these considerations it follows that, although market power reduces allocative efficiency, it is difficult to establish a clear relationship between market power and productive and dynamic efficiency. In many cases, the mere existence of a certain degree of market power helps competition. It is precisely the prospect of enjoying some market power (that is, of earning profits) that pushes firms to use more efficient technologies, improve the quality of their products or introduce new varieties of products. If antitrust agencies were to aim at eliminating or reducing market power whenever it appeared, this could have the harmful effect of eliminating firms’ incentives to innovate.

The capacity to set prices above marginal costs generates losses in social welfare or economic efficiency. However, there are reasons that explain why some industries have this capacity while others do not. Among them, there is the existence of economies of scale, which consist of those cases where the long-run average costs of a firm or industry reach their minimum —and thus optimal— point at a high level of output relative to market demand (Viscusi et al., 2018). This situation reflects the idea that it is sometimes more efficient for production to be carried out by a smaller number of firms, or even by a single firm.

On the other hand, there are economies of scope when it is cheaper for a single firm to produce two products together (joint production) than for more than one firm to produce them separately (OECD, 1993). For example, it may be less costly to provide an air service from point A to points B and C with a single aircraft than to have two separate flights, one going to point B and the other going to point C.

Although many factors can explain economies of scope, the presence of common inputs or complementarities in production is particularly important. Firms often seek to take advantage of economies of scope to produce and offer multiple products at lower cost.

The presence of economies of scale and scope has a significant implication for competition policy. If, as has been said, market power decreases with the number of firms in the industry, one might be tempted to conclude that the greater the number of firms, the greater the efficiency achieved.

However, in the presence of economies of scale, there is a trade-off. On the one hand, a larger number of firms implies more competition in the market and lower prices, which undoubtedly increases consumer surplus (allocative efficiency). On the other hand, it also entails duplication of fixed costs, which represents a loss in terms of productive efficiency. The net effect on welfare is a priori ambiguous (Motta, 2004).

The trade-off between allocative efficiency (lowering prices through competition) and productive efficiency (optimizing costs through economies of scale) suggests that a policy focused solely on maximizing the number of firms is often inadequate.

These considerations underscore a fundamental principle of antitrust: competition policy should aim to protect the competitive process itself, rather than shielding less efficient competitors from market forces.

The efficiencies arising from mergers deserve special consideration as they may serve as a critical counterweight to potential anti-competitive risks.

In this assessment, at least two dimensions are vital. On the one hand, productive efficiencies may be realized through economies of scale, scope, and density, as well as operational synergies. On the other hand, dynamic efficiencies—those relating to the development of new or improved products—enable firms to continuously enhance quality, service, and variety. It should be noted that these dynamic gains are often more closely associated with vertical or conglomerate mergers, where potential complementarities between firms are most pronounced.

On 10 May 2018, the Fiscalía Nacional Económica (“FNE”) blocked the acquisition of Alimentos Nutrabien S.A. (“Nutrabien”) by Ideal S.A. (“Ideal”), after concluding that the operation would have the ability to substantially reduce competition in the national markets for the manufacture and marketing of individual sponge cakes (“bizcochos”) and “alfajores” (two kinds of sweet snacks)

According to the FNE, entry and expansion conditions for competitors, as well as the remedies and efficiencies put forward by the parties, could not sufficiently mitigate the risks identified.

In particular, the parties claimed that the operation would generate cost reductions in terms of: (i) human resources, (ii) raw materials and (iii) logistics and distribution, thereby constituting static productive efficiencies. Regarding the first two items, the FNE concluded that the alleged efficiencies did not meet the requirements of verifiability and inherence. As for distribution processes, although the FNE partially acknowledged the existence of efficiencies, it considered that their impact would be insufficient to offset the greater market power that the merged entity would obtain.

Additionally, the parties argued that the operation would generate dynamic efficiencies arising from the increased geographic coverage and complementarity of their distribution channels. However, the FNE considered that there was insufficient evidence to substantiate these efficiencies.

Consequently, on 25 May 2018, the parties filed a special review appeal before the Tribunal de Defensa para la Libre Competencia (“TDLC”), seeking reversal of the decision and unconditional approval of the operation. Among other objections, the parties criticized the FNE for having applied an excessively strict verifiability standard, rejecting real efficiencies based on unfounded assumptions.

In this regard, the TDLC held that the information provided by the companies did indeed make it possible to verify efficiencies in the different distribution segments, as well as cost reductions —inherent to the operation— in wages and purchases of raw materials. It also questioned the FNE’s failure to consider potential efficiencies associated with products for which no risk of price increases had been identified. In the TDLC’s view, this meant that the efficiencies attributable to the operation were underestimated in the FNE’s analysis (para. 106).

On the basis of this reasoning, on 27 November 2018 the TDLC issued a judgment reversing the Prohibition Decision and approving the operation subject to mitigation measures.

Khemani, R. S. (1993). Glossary of industrial organisation economics and competition law. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Washington, DC: OECD Publications and Information Centre.

Leibenstein, H. (1966). Allocative efficiency vs. “X-efficiency”. The American Economic Review, 56(3), 392–415.

Motta, M. (2004). “Market Power and Welfare: Introduction”, in Competition Policy: Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Nicholas, T. (2003). Why Schumpeter was right: innovation, market power, and creative destruction in 1920s America. Journal of Economic History, 1023–1058.

Viscusi, W. K., Harrington Jr, J. E., & Sappington, D. E. (2018). Economics of Regulation and Antitrust. MIT Press.